Stanley Kunitz, The Art of Poetry No. 29

This interview took place during the winter of 1977 in Stanley Kunitz' brownstone in New York City's Greenwich Village. The apartment's ceilings are high. A number of modern paintings cover the height of the walls, fitted together in a great mosaic. Many are inscribed from artists of the New York School, the so-called Irascibles—Kline, Motherwell, Rothko, among them. Kunitz' wife is the distinguished painter, Elise Asher. Included in the collection are works which the poet confesses are his own—assemblages in the manner of Joseph Cornell composed of American folk-art items.

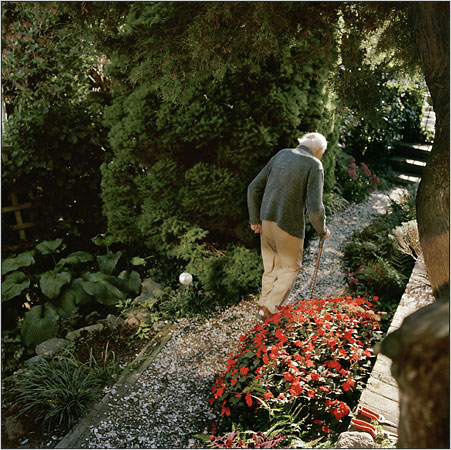

Kunitz, slightly stooped from a bout of arthritis, is now in his seventies. The summer before, at his Provincetown home on Cape Cod, he had been obliged to hire a gardener to help him with his weeding. He had been equally depressed at having to give up tennis: he could no longer play fiercely, and therefore it was not so much fun to play. But once, as he likes to recall, he could justly claim the tennis championship of the poetry world.

Certainly as regards his own craft Kunitz is in the first rank. “A reassurance as to what poetry can be in these times,” Richard Wilbur wrote of The Testing-Tree in 1971. The works which confirm this include Intellectual Things, Passport to the War, Selected Poems (which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1959), The Testing-Tree, and this year's collection, The Poems of Stanley Kunitz (1928-78).

In recent years Kunitz has edited The Yale Series of Younger Poets, served as Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, and taught at a number of universities, including Bennington, Brandeis, Yale, Princeton, and Columbia. He is currently senior professor in the graduate writing program at Columbia.

He is the recipient of many honors—a member of the American Academy of Art and Letters and a chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. Much of the year he spends in Cape Cod, where he works with the The Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, a resident community of young artists and writers. As is suggested in the interview which follows, he thinks highly of the farming profession.

The interview consolidates two long afternoons of taping. Late on the second day, after hours of talking with occasional sips of akvavit (the glasses were a gift from e.e. cummings), there came the voices of children echoing in the neighboring school courtyard. The poet switched on a light at his desk. Something that had been said induced him to search through a wilderness of papers for his copy of Hopkins. Instantly the book was opened to the proper page, and with a deep resonance, he began reading one of the Terrible Sonnets. This was the privileged moment for the interviewer. There is unfortunately no way to reproduce how Kunitz made the lines ring with emotion. But subsequently, when the tapes were played, the transcriber's dog, customarily indifferent to mechanical sounds, pricked up his ears at the harrowing hiss of the sonnet's last words: “The lost are like this, and their scourge to be / As I am mine, their sweating selves; but worse.”

INTERVIEWER

Is it an actual fact, as you indicate in “The Portrait,” that your father killed himself in a public park some months before you were born?

KUNITZ

I really didn't know too much about it. It floated in the air during my childhood. I never had any specific information. I didn't know the exact details until I happened to be in Worcester, reading. I went over to the city hall and asked for my father's death certificate and there it was. Age 39. Death by suicide. Carbolic acid. It would have torn his guts out. Strong stuff. I'm not sure how I learned he did it in a park. Maybe my older sister told me. That scene has always haunted me. There's a reference to it in a poem called “The Hemorrhage.” He becomes the fallen king, a Christ figure. My original title was “The Man in the Park.”

INTERVIEWER

Your father has always figured strongly in your poetry, and he continues to do so in The Testing-Tree. But I noticed here, for the first time, that your mother asserts a prominence.

KUNITZ

That's true. My mother has become closer to me in recent years. I understand her more than I did in the beginning. There were two strong wills in that household, hers and mine, so that our natural tensions were magnified. We held each other at a distance. She was the most competent woman I have ever known—I respected that. But it took years—after her death at eighty-six—for me to be touched by the beauty and bravery of her spirit.

INTERVIEWER

In The Testing-Tree, though, there isn't quite that portrait of her. She seems a woman of unforgiveness. She is “a grey eye peeping.” She guards you joylessly. In “The Portrait” she refuses to forgive your father for killing himself.

KUNITZ

Well, she was unconcessive in many ways. And it's true that she refused ever to speak to me about my father. She obliterated every trace of him. In her very last years, at my request, she began writing her memoirs. It's a remarkable document, which I will someday use in one form or other. She is fresh and vital writing about her childhood in Russia. And her emigration to this country. And her work as an operator in the sweatshops of New York's lower East Side. About everything until she moved to Worcester. Until she met my father. Then she froze, and wrote no more.

INTERVIEWER

Where in Russia did she come from?

KUNITZ

Lithuania.

INTERVIEWER

Did she speak Lithuanian or Russian at home?

KUNITZ

No. She spoke English, though she was twenty-three when she came here in 1890, with no knowledge of the language. She went to night school, read a good deal, educated herself.

INTERVIEWER

Was there much discussion of Russian writers in your house, as a boy?

KUNITZ

Not a great deal. But there was a good library. For that period and for that middle-class world, rather exceptional. There was a complete set of Tolstoy, complete Dickens, complete Shakespeare. An unabridged dictionary. A big illustrated Bible—both Testaments. A lot of history, history of all nations. The classic books. Gibbon. Goethe. Dante's Inferno illustrated by Gustave Doré. There was a sense of civilization there.

INTERVIEWER

You say very directly in “An Old Cracked Tune” that “my mother's breast was thorny, /and father I had none.” Is this comfortless situation based simply on her attitude toward your father or did it arrive out of your relationship with her?

KUNITZ

My mother was a working woman, absent all day—in that era a rare phenomenon. She was one of the pioneer business women, a dress designer and manufacturer. I was always left in the care of others and didn't have an intimate day-to-day contact with her. When she came home in the evening, she was tired and easily vexed, impatient with my moodiness. She was not one to demonstrate affection physically—in fact, I don't recall ever being kissed by her during my childhood. Yet I never doubted her fierce love for me. And pride in me for my little scholastic triumphs and early literary productions.

INTERVIEWER

My favorite poem of yours is “King of the River,” and I believe my reason is that the salmon, ostensibly the subject of the poem, is half-fish, half-Kunitz. Could we talk a little about how the poem came into being?

KUNITZ

What triggered “King of the River,” I recall, was a brief report in Time of some new research on the aging process of the Pacific salmon. I wrote the poem in Provincetown one fall—my favorite writing season. The very first lines came to me with their conditional syntax and suspended clauses, a winding and falling movement. The rest seemed to flow, maybe because I'm never very far from the creature world. Some of my deepest feelings have to do with plants and animals. In my bad times they've sustained me. It may be pertinent that I experienced a curious elation while confronting the unpleasant reality of being mortal, the inexorable process of my own decay. Perhaps I had managed to “distance” my fate—the salmon was doing my dying for me.

A poem has secrets that the poet knows nothing of. It takes on a life and a will of its own. It might have proceeded differently—towards catastrophe, resignation, terror, despair—and I still would have to claim it. Valéry said that poetry is a language within a language. It is also a language beyond language, a meta-medium—that is, metabolic, metaphoric, metamorphic. A poet's collected work is his book of changes. The great meditations on death have a curious exaltation. I suppose it comes from the realization, even on the threshold, that one isn't done with one's changes.

INTERVIEWER

Isn't it true that a poet has preferences among his own poems in the same way that he has preferences among the poems of other poets? That specialness isn't always based on sheer quality. You yourself have defended a line from “Father and Son” that critics have complained was obscure or ugly even. If I remember, the line went: “ . . . The night nailed like an orange to my brow.” But you felt that nails and fruit have had a long history in your consciousness and that you didn't give a damn whether someone liked it or not. Do you have any of that obstinate fondness for this poem?

KUNITZ

Some days I have an obstinate fondness for all my poems. Other days I dislike them intensely. I'll concede that the poems of mine that stay freshest for me in the long run are the archetypal ones, of which “King of the River” is undoubtedly an example. I mean archetypal in the Jungian sense, with reference to imagery rooted in the collective unconscious. I am no longer attracted to or tempted by the sort of metaphysical abstraction that led me in my youth to write—somewhat presumptuously, it seems to me now—of daring “to vie with God for his eternity.” The images I seek are those derived from bodily immersion in what Conrad called “the destructive element.” That salmon battering towards the dam . . ..

INTERVIEWER

Is this a Christian God you're contending with?

KUNITZ

Call Him the God of all gods. I have no sectarian faith.

INTERVIEWER

Roethke mentions in one of his letters that “Stanley Kunitz says I am the best Jewish poet in the language.” I was wondering what you meant by that.

KUNITZ

It sounds like me, but I don't remember the occasion. I was probably just teasing him about being guilt-ridden and full of moral imperatives. Besides, he had inherited some anti-Semitic reflexes from his Prussian ancestors.

INTERVIEWER

I'm trying to find a delicate way of asking you to comment on a rather offensive characterization of you by Harold Bloom. He includes you with several poets who he feels have evaded their Jewish heritage in their poetry.

KUNITZ

Cripes!

INTERVIEWER

Insofar as your poems are morally conscious they may be construed to be Jewish. The son in “Father and Son” asks his absent father to “teach me how to work and keep me kind.” One great aim of your work is to discover the ethical content of your own unconscious.

KUNITZ

It's obvious that Jewish cultural aspiration and ethical doctrine entered into my bloodstream, but in practice I am an American freethinker, a damn stubborn one, and my poetry is not hyphenated. I said a few minutes ago that I had no religion, but I should have added that I have strong religious feelings. Moses and Jesus and Lao-tse have all instructed me. And the prophets as well, from Isaiah to Blake—though Blake is closer to me. I had never thought of it before, but it's true that three of the poets who most strongly influenced me—Donne, Herbert, Hopkins—happen to have been Christian churchmen.

INTERVIEWER

Bloom's point was that the Jewish poet cannot offer his wholehearted surrender to a Gentile precursor.

KUNITZ

Bloom should ask himself why all his poets are WASPs.

INTERVIEWER

In the years before 1959, when you were awarded the Pulitzer Prize, you were relatively obscure as a poet. Can I have your reasons for that?

KUNITZ

I am not and never was a prolific or fashionable poet. For a long time I lived apart from the literary world, in rural isolation. During my middle years my poems were said to be too dark and obscure, though they seem quite intelligible now. To this day I've had very little serious critical attention. Maybe I don't know how lucky I've been!

INTERVIEWER

I detect certain mannerisms of Eliot in some of the early poems.

KUNITZ

Eliot invented a tone of voice and put his stamp on the metaphysical mode. In my generation, the next after his, one would have to be a fool not to learn something from him. But in fundamental respects I rejected what he stood for. From the beginning I was a subjective poet in contradiction to the dogma propounded by Eliot and his disciples that objectivity, impersonality, was the goal of art. Furthermore, I despised his politics. It's ironic that a generation later, when confessional poetry, so-called, became the rage, I was classified as a late convert to the confessional school. That made me laugh and shudder. My struggle is to use the life in order to transcend it, to convert it into legend.

INTERVIEWER

What were some of the other pressures that brought about the looser style of the poems in The Testing-Tree?

KUNITZ

The language of my poetry's always been accessible, even when the syntax was complex. I've never used an esoteric vocabulary, though some of my information may have been special. I believe there is such an intrinsic relationship between form and content that the moment you start writing a poem in pentameters you tend to revert to an Elizabethan idiom. “Night Letter,” for example, is rhetorically an Elizabethan poem. What strikes me, as I read and reread the poetry and prose of the Elizabethans, is that they had a longer breath unit—their language was still bubbling and rich in qualifiers, in adjectives and adverbs. The nouns and verbs of Shakespeare couldn't, by themselves, fulfill the line and give it enough richness of texture for the Renaissance taste. I acquired a taste for that kind of opulence of language, but as the years went on I began to realize that my breath units didn't require so long a line. By my middle period I was mainly working with tetrameters, which eliminated at least one adjective from every line. In my current phase I've stripped that down still more. I want the energy to be concentrated in my nouns and verbs, and I write mostly in trimeters, since my natural span of breath seems to be three beats. It seems to me so natural now that I scarcely ever feel the need for a longer line. Sometimes I keep a little clock going when people talk to me and I notice they too are speaking in trimeters. Back in the Elizabethan Age I'd have heard pentameters.

INTERVIEWER

Does the increased accessibility of the poems in The Testing-Tree indicate a significant change in your aesthetic?

KUNITZ

At my age, after you're done—or ruefully think you're done—with the nagging anxieties and complications of your youth, what is there left for you to confront but the great simplicities? I never tire of birdsong and sky and weather. I want to write poems that are natural, luminous, deep, spare. I dream of an art so transparent that you can look through and see the world.

INTERVIEWER

Occasionally a poem of yours—“The War Against the Trees” is an example—will sound mock heroic on the page, and I am surprised that the tone in which I've heard you read it is not at all mock heroic.

KUNITZ

Irony is one of the ingredients there—but I shouldn't call it mock heroic.

INTERVIEWER

Take a line like this: “ . . .the bulldozers, drunk with gasoline, /Tested the virtue of the soil.” Or: “All day the hireling engines charged the trees, . . . forcing the giants to their knees.” It's the magnification of the event and the personification of the bulldozers and the trees.

KUNITZ

Well, I suppose that for me the rape of nature is an event of a certain magnitude. My feeling for the land is more than an abstraction. I've always been mad about gardening, and used to think, when I was struggling to survive, that I could end my days quite happily working as a gardener on some big estate. In Provincetown I tend my terraces flowering on the bay. I'm out there grubbing every summer morning. The man in one of my poems who “carries a bag of earth on his back” must be my double.

INTERVIEWER

One doesn't think of you as a pastoral poet, but you draw a good deal of your sustenance from the natural world. For most of your adult life you've chosen to live in the country.

KUNITZ

With the first five hundred dollars I saved after coming to New York I bought a hundred-acre farm on Wormwood Hill in Mansfield Center, Connecticut, and moved there with my first wife. That was in 1930. I loved the woods and fields and the grand old eighteenth-century house, with its gambrel roof. But we were poor, and living conditions were primitive, without electricity or central heating or even running water. Eventually I made the improvements that the house required—mostly with my own hands—but I couldn't save the marriage. Later, for the span of my second marriage, I lived in Bucks County, Pennsylvania—beautiful country. That's the locale of “River Road.” I've always needed space around me, a piece of ground to cultivate, and the feel of living creatures. I'm never bored in the country. Very few of my poems deal with urban situations.

INTERVIEWER

What about the need for friendship and literary stimulation?

KUNITZ

I didn't realize what I was missing until one evening Ted Roethke drove down to New Hope from Lafayette and knocked at my door, unannounced, with a copy of Intellectual Things in his hand. It astonished me that this big, shambling stranger knew my poems by heart.

INTERVIEWER

Roethke at this time had published only a few poems?

KUNITZ

He had published practically nothing, but was working on the poems that eventually became. Open House. That was a saving relationship for both of us. I sensed he needed me even more than I needed him.

INTERVIEWER

You were both lonely. But he sought somebody out.

KUNITZ

He was much more aggressive than I, more socially ambitious, and he soon had a world of literary friendships, of which I would hear when he came to see me. He would tell me about Louise Bogan and Leonie Adams and Rolfe Humphries and, a bit later, Auden and all the others that he sought out and gathered to him. But he did not bring us together. His policy was to keep his friends apart.

INTERVIEWER

Were you a loner on some principle or were you naturally shy?

KUNITZ

As a young man I was preternaturally shy. For years it was difficult for me to reach out to others. I'd lived such an inward life for so long. I think I'm more open with people now.

INTERVIEWER

In your early poems there are fairly frequent references to your youth as being a period of despair, as if you resented it. In one you say, “ . . . innocence betrayed me in a room / of mocking elders . . .”

KUNITZ

I've been through many dark nights, but the guilts I've expressed aren't meant to be interpreted confessionally. Somebody once asked me, quite bluntly, what it was I felt so guilty about. I replied, “For being fallible and mortal.” Does that make me sound terribly glum? Believe me, I've had my share of joys. And I'm still ready for more.

INTERVIEWER

You had an unhappy period in the army during World War II. What were the circumstances?

KUNITZ

Briefly, I was drafted, just short of my thirty-eighth birthday, as a conscientious objector, with moral scruples against bearing arms. My understanding with the draft board was that I would be assigned to a service unit, such as the Medical Corps. Instead the papers on my status got lost or were never delivered, and I was shuttled for three years from camp to camp, doing KP duty most of the time or digging latrines. A combination of pneumonia, scarlet fever, and just downright humiliation almost did me in. While I was still in uniform, Passport to the War, my bleakest book, was published, but I was scarcely aware of the event. It seemed to sink without a trace.

INTERVIEWER

In the period before you went into the army, what magazines were you publishing in?

KUNITZ

I was publishing very little then. Witty, elegant, Audenesque poems were in demand then, not mine. I was lucky to get my book published at all. Practically every major publishing firm rejected it before Holt took it. I had the same unflattering experience with my Selected Poems, fourteen years later, before Atlantic accepted them.

INTERVIEWER

Aside from Roethke, did you have any staunch supporters?

KUNITZ

I had more than I knew, but no lines of communication between us. Imagine my surprise to learn, on my discharge from the army in '45, that I had been awarded a Guggenheim fellowship, for which I had never applied. When I inquired how it could have happened, I was told that Marianne Moore, whom I wasn't to meet until years later, had been my intercessor.

INTERVIEWER

At forty you still thought of yourself as a stranger?

KUNITZ

I'm reminded of a passage in a letter from Henry James in reply to a young admirer of his. This was late in his life. “You ask me from what port I embark? That port is my essential loneliness.”*

INTERVIEWER

Your earlier poems have been accused—I should say that is the right word—of being overly intellectual . . .

KUNITZ

[laughs] . . .which is nonsense.

INTERVIEWER

But when one dwells on the paradox that such work as you have produced is urbane only in its complexity, not in its concerns, then one begins to see that there is something real in your choice to live apart from the city. Perhaps there is something about much thought, small conversation, and the endless blue of country skies that stunts the smart aleck and develops one's mystical sense, as if one is left without a language adequate for wonder. In the language that one does find, there is both great strain and mystical attainment.

KUNITZ

I am happy that you made this comment because that strain in my work that you refer to as mystical—a suspect word—is one that I don't think anybody has ever really noted before or commented on. One of my primary convictions is that I am not a reasonable poet.

INTERVIEWER

One of your poems—“The Science of the Night”—has a passage: “We are not souls but systems, and we move / In clouds of our unknowing”. Is that a direct reference to the text by the medieval religious mystic?

KUNITZ

Yes. The Cloud of Unknowing—haunting phrase. But, sure, I think that what we strive for is to move from the world of our immediate knowing, our limited range of information, into the unknown. My poems don't come easy—I have to fight for them. In my struggle I have the sense of swimming underwater towards some kind of light and open air that will be saving. Redemption is a theme that concerns me. We have to learn how to live with our frailties. The best people I know are inadequate and unashamed.

INTERVIEWER

Can you say something about how you manage to find “the language that saves”?

KUNITZ

The poem in the head is always perfect. Resistance starts when you try to convert it into language. Language itself is a kind of resistance to the pure flow of self. The solution is to become one's language. You cannot write a poem until you hit upon its rhythm. That rhythm not only belongs to the subject matter, it belongs to your interior world, and the moment they hook up there's a quantum leap of energy. You can ride on that rhythm, it will carry you somewhere strange. The next morning you look at the page and wonder how it all happened. You have to triumph over all your diurnal glibness and cheapness and defensiveness.

INTERVIEWER

One of my ideas about your poetry is that there are two voices, arguing with each other. One is the varied voice of personality, the voice that speaks in the context of a dramatic situation. The other is an internal voice, the voice that's rhythm. It governs a poem's movement the way the waves govern the movement of a boat—seldom do the two want to go in the same direction.

KUNITZ

The struggle is between incantation and sense. There's always a song lying under the surface of these poems. It's an incantation that wants to take over—it really doesn't need a language—all it needs is sounds. The sense has to struggle to assert itself, to mount the rhythm and become inseparable from it.

INTERVIEWER

Would you say that rhythm is feeling, in and of itself?

KUNITZ

Rhythm to me, I suppose, is essentially what Hopkins called the taste of self. I taste myself as rhythm.

INTERVIEWER

How wide a variety of rhythms do you feel?

KUNITZ

The psyche has one central rhythm—capable, of course, of variations, as in music. You must seek your central rhythm in order to find out who you are.

INTERVIEWER

So you would agree you could say about music that Bach's central rhythm is devotional and Mozart's is gay, sunny and exuberant. How would you define your own rhythm in these terms?

KUNITZ

Mine, I think, is essentially dark and grieving—elegiac. Sometimes I counterpoint it, but the ground melody is what I mostly hear.

INTERVIEWER

With respect to rhythm, could you discuss your term “functional stressing”?

KUNITZ

Functional stressing is simply my way of coping with the problem of writing a musical line that isn't dependent on the convention of alternating slack and stressed syllables. What I usually hear these days is a line with three strong stresses in it—that's my basic measure. I don't make a point of counting stresses—the process is largely unconscious, determined by my ear. A line can have any number of syllables, and sometimes it will add or eliminate a stress. Rhythm depends on a degree of regularity, but the imagination requires an illusion of freedom. This functional stressing is related to Hopkins' concept of sprung rhythm. Except that he understood sprung rhythm —mistakenly, I believe—to be a falling rhythm, whereas my rhythm is usually rising. Furthermore, functional stressing dispenses with the notion of the metrical foot as a unit in the line. The system of stresses is the organizing principle of a poem. I tend to dwell on long vowels and to play them against the consonants; and I love to modulate the flow of a poem, to change the pace, so that it quickens and then slows, becomes alternately fluid and clotted. The language of a poem must do more than convey experience: it must embody it.

INTERVIEWER

Is this what you look for in the poems of others, that feeling of there it “happened” to him, that feeling of oneness with his subject? Take a writer like D.H. Lawrence, who's utterly unlike you.

KUNITZ

Nevertheless, he's a poet I admire. I think of “The Snake” or, better still, “The Ship of Death”—his ecstatic funeral song. He's a dying man, sailing out towards the unknown—a rocking, redundant movement—and you're on board with him, sharing his destiny, a passenger on the same ship, which is so real you feel the glow of the sunset and the coming of the night.

INTERVIEWER

And that transcends any literary consideration?

KUNITZ

It transcends it. You mustn't let the aesthetic of a period determine for you what's good or bad in poetry.

INTERVIEWER

That's why it must be so annoying for you to have critics praise you for your skillful craft.

KUNITZ

Oh, I hate that. I take it as a put-down. Unless craft is second nature, it means nothing. Craft can point the way, it can hone an instrument to a fine cutting edge, but it's not to be confused with an art of transformation, that magical performance.

INTERVIEWER

Frost talks about the poet, or himself rather, as a performer, as an athlete is a performer. In what sense do you mean that writing is a performance?

KUNITZ

A trapeze artist on his high wire is performing and defying death at the same time. He's doing more than showing off his skill; he's using his skill to stay alive. Art demands that sense of risk, of danger. But few artists in any period risk their lives. The truth is they're not on a high enough wire. This makes me think of an incident in my childhood. In the woods behind our house in Worcester was an abandoned quarry—you'll find mention of it in “The Testing-Tree.” This deep-cut quarry had a sheer granite face. I visited it almost every day, alone in the woods, and in my magic Keds I'd try to climb it, till the height made me dizzy. I was always testing myself. There was nobody to watch me. I was testing myself to see how high I could go. There was very little ledge, almost nothing to hold on to. Occasionally I'd find a plant or a few blades of tough grass in the crevices, but the surface was almost vertical, with only the most precarious toehold. One day I was out there and I climbed—oh, it was a triumph!—almost to the top. And then I couldn't get down. I couldn't go up or down. I just clung there that whole afternoon and through the long night. Next morning the police and fire department found me. They put up a ladder and brought me down. I must say my mother didn't appreciate that I was inventing a metaphor for poetry.

INTERVIEWER

In “The Testing-Tree,” when you threw the three stones against the oak, you don't mention how many hit. If you hit once, it was for love; twice, and you would be a poet; three times, and you would live forever.

KUNITZ

I got awfully efficient. In the end I almost never missed. I've always excelled at hand-and-eye coordination, any sort of ball game. That makes me think of a game I used to play with Roethke. I put a little waste basket at one end of the room, and then we'd try to pitch tennis balls into it from the opposite corner. Each successful pitch was worth a dime. If I made ten shots in a row and he made three, he owed me 70¢. Well, I was really phenomenal at this, and I made a small fortune from Roethke. In fact, he refused to play with me any more because he said I was practicing during his absence. It's true enough. Sometimes I still play that game against myself.

INTERVIEWER

I recall a poker game last summer with Mark Strand, B. H. Friedman, Daniel Halpern, and some painters. You hadn't played in twenty years. If there is an analogy between sports—games—and poetry, what or whom is the poet competing against?

KUNITZ

Eternity. A losing battle, for in that abyss all egos, cities, nations, histories are buried. Even Shakespeare will ultimately be forgotten. The best a poet can hope for is to be remembered for a while, to pass from one generation into another, to have some young person in another age open to a page and say, “How beautiful!” or “How true! He must have been like me.”

INTERVIEWER

With respect to what you have just said, how did you sustain your ambition during your years of isolation?

KUNITZ

If I inherited my father's vulnerability, I also inherited my mother's pride and stubbornness. During those years when I was most obscure and when I had no reputation at all, I never really doubted myself or thought I was a finished poet. I knew that the struggle was still going on inside me. I was still fighting for that language, still full of curiosity, of love and hate and all the emotions that make one know one is alive. So when a few lucky things happened, I wasn't overwhelmed. It seemed the natural order of things. Nothing to be hilarious about. If one lives in the world of struggle for language and truth, the things that happen outside are not terribly important. The same honor given one year to you goes the next year to some clown.

INTERVIEWER

How did you get involved with teaching?

KUNITZ

When I was in the service I got a letter from Lewis Webster Jones, the president of Bennington, offering me a teaching job when I got out of the Army. I was staggered. I had never taught before. I'd been free-lancing and editing for The H.W. Wilson Co., but I hadn't taught at all and I couldn't understand why I was being asked to come and teach at Bennington. It turned out that Roethke, who had been teaching there, had had a violent breakdown and had locked himself into his cottage, threatening anybody who came near him, especially the president. He was finally induced to carry on a conversation. He said he knew the jig was up—he'd have to leave. But he'd come out and be peaceful on one condition—that they invite me to take his place.

INTERVIEWER

Did you look forward to this?

KUNITZ

I'd always been hungry to teach, though I thought I never would after my initial rejection at Harvard.

INTERVIEWER

Could you go into that?

KUNITZ

At Harvard I stayed on for my Masters with the thought of becoming a member of the faculty. It seemed to me a not unreasonable expectation, since I had graduated summa cum laude and won most of the important prizes, including the Garrison Medal for Poetry. When I inquired about it, the word came back from the English faculty that I couldn't hope to teach there because “Anglo-Saxons would resent being taught English by a Jew.” I was humiliated and enraged. Even half a century later I have no great feeling of warmth for my alma mater. Of course that was in the dark ages of the American Academy. A few years after I left, Jews were no longer considered to be pariahs. From this vantage point I'm glad I didn't stay and become an academician. All those years of struggle taught me a great deal about the vicissitudes of life. My scrambling for survival kept me from being insulated from common experience. It certainly fed my political passions.

INTERVIEWER

What did you do after you left Harvard?

KUNITZ

I went back to Worcester and became a staff reporter on the Worcester Telegram. I had been a summer reporter on the Telegram since my sophomore year, when I wrote an impertinent letter to the editor, saying that I thought the paper could use somebody who knew how to write. As proof of my literary prowess, I enclosed an impressionistic panegyric on James Joyce—this was in 1923. In a few days, much to my amazement, I received a letter from Capt. Roland Andrews, editor-in-chief, saying that by God I could write and a job was mine for the asking. As a full-time member of the staff I became assistant Sunday editor and wrote a literary column and did some features. Then I was assigned to the Sacco-Vanzetti case. I soon saw that a terrible injustice was being perpetrated. My particular assignment was to cover the judge, Judge Webster Thayer, a mean little frightened man who hated the guts of these “anarchistic bastards.” He could not conceivably give them a fair trial. I was so vehement about this miscarriage of justice, so filled with it, that around the newspaper office they used to call me “Sacco.” After the executions, I became obsessed with the notion that Vanzetti's eloquent letters should be published and received permission to see what I could do about it. I gave up my job on the Telegram and went to New York alone. I had nothing, no money, no friends. I made the rounds of the publishing houses, but nobody would touch the book. The whole country was in the grip of one of its periodic Red scares. I was virtually penniless by the time I landed a job with The H. W. Wilson Company.

INTERVIEWER

You quit your job with the Worcester Telegram expressly to find publication for the letters?

KUNITZ

I sensed it was time for me to leave. Curiously, I was twenty-three when I came to New York, the same age as my mother when she landed at the immigrant station on Castle Garden.

INTERVIEWER

Your career seems larger at both ends. You first published when you were quite young and now, as you have put it, you're threatening to become prolific.

KUNITZ

I like the verb “threatening.”

INTERVIEWER

Who were the critics who helped you keep faith in yourself?

KUNITZ

The blunt truth is that I owe damn little to critics. Yvor Winters praised my first book, but then I lost him because he accused me of betraying the iambic foot. Mark Schorer and Jean Hagstrum and Ralph Mills have written commentaries that I appreciate. Roethke was my advocate almost from the start, when he himself was struggling for recognition, but I don't think of him as a critic. The same holds true for Lowell and Wilbur and Eberhart, who have been friends since the late fifties. I mustn't forget to mention the late Henry Rago, editor of Poetry, a dear friend, who encouraged me when I most needed encouragement, and who was largely responsible for the recognition that came to me with the publication of Selected Poems. None of the critics associated with the New Criticism paid any attention to me then. Robert Penn Warren and Allen Tate befriended me later.

INTERVIEWER

What sort of function or role are you trying to accomplish in your own criticism?

KUNITZ

I'm not programmatic. I suppose I try to establish the connections between language and action, aesthetics and moral values, the individual and society.

INTERVIEWER

Your pieces on other poets are invariably sympathetic at heart.

KUNITZ

I've made a point of not writing about poets with whom I am not sympathetic. There's plenty of negativism around about poets. I don't feel any need to contribute more. Of course I recognize differences. For example, my essay on Robinson Jeffers attacks his political insensibility about Hitler, but at the same time it is written with true respect for his achievement as a poet. If you understand a poet's key images, you have a clue to the understanding of his whole work. I wish criticism would spend more time in the intimate pursuit of those central images. That's a more productive concern than ratings and influences.

INTERVIEWER

In the tone you take in your reviews do you feel you're speaking directly to the poet under review?

KUNITZ

I think so. In my personal experience the most helpful criticism has been from fellow poets. The best criticism is addressed to the poet over the heads of the public. It's not judgmental but collaborative. It aims to help the poet find his own self in the course of his sometimes obscure progress, where he is dark even to himself. The analogous relationship is that of coach to athlete. You're all for your man to score, to win; you don't jeer at him. “Bad one! Bad one! That was a terrible shot!” Recently at the Guggenheim, after I had introduced Robert Penn Warren, with heartfelt praise for his new Selected volume, he remarked to the audience: “I'm going to tell you a great secret, about how to get on as a poet. Have fine poets for your friends!”

INTERVIEWER

What is the origin of your early imagery of spikes and cones and spheres?

KUNITZ

I don't know. It could be religious, or cubistic, or scientific. I haven't mentioned that I had an apprenticeship with Alfred North Whitehead during my last year at Harvard. He was giving an advanced course in the nature of the physical universe. I didn't have the prerequisites, but I wanted very much to be one of the handful permitted to study with him. I went to see Whitehead. He asked me why I wanted to be in his group. I said, “I'll give you two reasons. I admire you extravagantly and I'm a poet.” He said, “You're in.” I learned a lot from him.

INTERVIEWER

You also met the “Moon Man” in Worcester?

KUNITZ

Dr. Robert H. Goddard. Yes. This was in the spring of 1926 while I was on the Telegram. One day the city editor said to me, “There's a crazy man in town playing around with rockets. Why don't you go over and see him?” So I went over to Clark University where Goddard was professor of physics. I may have been the first person ever to interview him. This was shortly after he had made the great experiment outside the city limits of Worcester—in an open field in Auburn he had fired the first liquid-fueled rocket. He told me about this with quiet intensity. I said, “How high did it go?” And he said, “184 feet in 2.5 seconds.” “Is that all?” I said. His voice turned a little shrill, “Young man, don't you see? It's all solved! We'll make it to the moon! Because the principle is right, don't you see, don't you see?” He went to his blackboard. A little man, very professorial looking, completely obsessed with his calculations and diagrams. I have an unpublished poem about this encounter. He made me feel somehow connected with him, as though both of us were shooting for the moon, in different ways.

INTERVIEWER

His story was your story?

KUNITZ

I suppose I made it mine. That's the way with the imagination.

INTERVIEWER

Not many poets writing during the early years of your career were attracted to science?

KUNITZ

And no wonder. After a quarter of a century I still have to explain to audiences what I am doing with the metaphor of the red shift in “The Science of the Night.” Such terminology ought to be just as common knowledge as the myths were in ancient Greece. The vocabulary of modern science is fascinating—I read everything I can find about pulsars and black holes and charm and quarks—but, by and large, the vocabulary remains exclusive and specialized. The more we know about the universe, the less understandable it becomes. The classic world had more reality than ours. At least it thought it understood what reality was. In 1948, I recall, Niels Bohr visited Bennington and drew a neat picture of neutrons and protons on the blackboard. In the question period that followed I asked him, “Is this really the structure of the atom, or is it your metaphor for the present state of our information about it?” He preferred then not to accept that distinction. Today a diagram of the atom would look vastly different, more complicated, and I would not need to repeat the question.

INTERVIEWER

Scientists think their metaphors are not heuristic.

KUNITZ

The popular impression is that their metaphors are real and the poet's metaphors are unreal. But both are trying to find metaphors for reality. It always haunts me that human beings were accumulating experience and knowledge in their bodies before they had a language. That's where our oldest wisdom is. The language of the imagination is a body language. That's why poetry is resistant to abstractions.

INTERVIEWER

Why do you suppose the metaphors of scientists are taken with much more seriousness than those of poets?

KUNITZ

Because we live in a pragmatic society, and the effects of science are evident, whereas the consequences of poetry are invisible. How many truly believe that if poetry were to be suppressed, the light of our civilization would go out?

INTERVIEWER

If there are few serious readers of poetry, how is its light disseminated?

KUNITZ

Largely it's disseminated among the young. A sizable fraction of the youth in our universities read poetry, hear poets and are excited by them. Any poet who travels across the country knows this to be true. Many of these students will go out into the world and never read another book of poems, but if only a fraction of them retain their interest, it will be a significant change for the better. It occurs to me that, though poets don't have large readership, their product in diluted form comes down to the mass population—in popular music, popular song, in all the areas of commercialized art. Popular art in this country today is a reduced, somewhat degraded form of high art, in contrast to other epochs, when popular art fed high art. Writers of the ballads inspired the poets of the Romantic movement. Nursery rhymes entered into the imagination of the poets in all centuries. Now we are getting the reverse process—high art, in its diluted state, touches everybody. Bob Dylan couldn't have existed if Dylan Thomas hadn't existed before him.

INTERVIEWER

Since the media occupy a paradoxical relationship to art as a diluter, but also as a disseminator, are they an ally of art?

KUNITZ

They could be, but they aren't. Yet every once in a while something comes along to remind you of possibilities. Haley's Roots on TV, for example, which stirred a nation's conscience—at least for a few nights. It gave white masters an opportunity to redeem themselves through guilt. Incidentally, I was in Ghana and Senegal last spring. The curious thing that struck me was that young African poets are trying to forget their tribal and colonial past. The main collective effort is to move into high technology and to overleap centuries of industrial backwardness. The poets want to jump smack into the Western world and write like Westerners. They study and imitate us. One young Ghanaian told me he felt guilty about not writing in his tribal language, but he scarcely knew it and it was too difficult to master for literary purposes. In our culture, we have a counter-phenomenon. Our poets are trying to rediscover our tribal past, the bonds that hold us together. The search back into the roots of our common life is an archetypal journey. We have to go back and reconstruct the foundation myths, so they will live again for us. Poetry is tied to memory. As we grow older, our childhood returns to us out of the mists. I may be mistaken, but my impression is that early in the century—I'm speaking in general terms—a child had fewer advantages, but he was more innocent, more hopeful, more ambitious than his grandchildren today. We really believed then that society was on our side.

INTERVIEWER

And now?

KUNITZ

Well, the young people I know have neither innocence nor guilt nor faith in the future. They feel they're not responsible for their inheritance. Of course, there are exceptions.

INTERVIEWER

It has lately crossed my mind that being a champion or a genius is simply a matter of accident, like being born a grey horse instead of a brown horse.

KUNITZ

Talent is almost the cheapest thing we have. The question is one of character, alertness. I like a remark of Pasteur's: “Chance favors only the prepared mind.”

INTERVIEWER

You've lived most of your life outside the poetry establishment. Do you consider yourself to be a part of it now? Has your attitude toward it changed?

KUNITZ

I wish I knew what the poetry establishment was. It's curious that nobody speaks of the fiction establishment. Poets don't get their rewards in the marketplace, so maybe they tend to take honors and prizes and the illusion of power much too seriously. There's a heavy accumulation of bile in that famous Pierian spring. Some poets seem to think they have to kill off their predecessors in order to make room for themselves. If you live long enough and receive a bit of recognition, you're bound to become a target. The only advantage of celebrity I can think of is that it puts one in a position to be of help to others. The phrase “community of poets” still has a sweet ring to me.

INTERVIEWER

For sheer good company, you seem to prefer painters to poets.

KUNITZ

I count myself lucky to be married into their world. I envy them because there is so much physical satisfaction in the actual work of painting and sculpture. I'm a physical being and resent this sedentary business of sitting at one's desk and moving only one's wrists. I pace, I speak my poems, I get very kinetic when I'm working. Besides, I love the social and gregarious nature of painters. Poets tend to be nervous and competitive and introverted. My image of discomfort is three poets together in a room. My painter-friends—among them Kline and De Kooning and Rothko and Guston and Motherwell—were enacting an art of gesture to which I responded. When I insist on poetry as a kind of action, I'm thinking very much in these terms—every achieved metaphor in a poem is a gesture of sorts, the equivalent of the slashing of a stroke on canvas.

INTERVIEWER

You have produced some sculpture—wire sculpture and assemblages.

KUNITZ

Sometimes I feel I'm a sculptor manqué. I love working with my hands. In my garden, my woodworking. My hands want to make forms. Though my poems often deal with the time sense, I'm inclined to translate that into metaphors of space. I like to define my perimeters. I want to know where a poem is happening, its ground, its footing, how much room I have to move in.

INTERVIEWER

You organize a poem spatially?

KUNITZ

It's one of the ways a poem of mine gets organized. I follow the track of the eye—it's a track through space.

INTERVIEWER

The Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, which you helped start, would seem to be a reflection of your concern with making a community of artists and writers.

KUNITZ

Art withers without fellowship. I recall how grievously I missed the sense of a community in my own youth. In a typical American city or town poets are strangers. If our society provided a more satisfying cultural climate; a more spontaneous and generous environment, we shouldn't need to install specialized writing workshops in the universities or endow places like Yaddo or MacDowell or Provincetown. In Provincetown we invite a number of young writers and visual artists from all parts of the country to live at the Center for an extended period, working freely in association. Our policy is not to impose a pattern on them, but to let them create their own. In practice, instead of becoming competitive, they soon want to talk to one another about their work problems, they begin to share their manuscripts and paintings, they arrange their own group sessions, they meet visiting writers and artists and consult with them, if they are so inclined. Most who come for the seven-month term are loathe to leave. Many of them stay on as residents of the town.

INTERVIEWER

What about the situation in Iowa?

KUNITZ

Iowa has the reputation of producing a recognizable brand of poetry. Call it Corn Fed Surrealism. But it can't be wholly true, for I picked three Iowa graduates for the Yale Series of Younger Poets without having the faintest notion of their pedigree. Peter Klappert, Michael Ryan, Maura Stanton—they don't sound alike at all. In their case, certainly, talent overcame education.

INTERVIEWER

You've resigned this year from your editorship of the Yale Series?

KUNITZ

Yes. Eight years is long enough. Close to a thousand book-length submissions a year. It's a heavy chore. The feeling at the Press was that it was time to appoint an editor who didn't have Eastern connections. I'm happy indeed that Dick Hugo is to be my successor. But I must add, to set the record straight, that out of my eight choices only three were Easterners. Coincidentally, here's this letter on my desk from Dick, out in Montana—it just came today. He says: “I used to think there was an 'Eastern Establishment' until I went East and found people far more critical of each other than we dare to be out here. If there ever is any 'Establishment,' chances are it will be Western, formed out of loneliness.” It confirms what I said to you earlier on that subject.

INTERVIEWER

Can you comment on the quality of the work of young poets?

KUNITZ

I hate to generalize, but I'll make a stab at offering a few broad conclusions. My first and main observation is that no earlier generation has written so well, or in such numbers. But it's a generation without masters: dozens of poets are writing at the same level of accomplishment. My explanation is that what we're experiencing is the democratization of genius. It's also clear that few poets have much of anything to say. Practically the only exceptions are the liberated women, who have the authentic passion of a cause. It's no accident that my first five Yale selections were men, my last three female. Another point is that few young poets have mastered traditional prosody. The result is that they don't really know how to make language sing or move for them. There's a modicum of music in most of what's being written today. They're not testing their poems against the ear. They're writing for the page, and the page, let me tell you, is a cold bed.

INTERVIEWER

Among your recent work, “Three Floors” stands out for its musical effects.

KUNITZ

Studs Terkel, who interviewed me last fall in Chicago, told me it was one of his favorites. He had me read it while someone played Warum in the background—on tape, of course. A little corny, perhaps, but it was quite moving to hear that music, which I hadn't really heard since my childhood. I realized that I had actually written the poem to that melody. The poem goes back to more formal patterns. It's the only rhymed stanzaic poem in The Testing-Tree. And not because I planned it that way, but simply because it came to me that way. It would have been a lie to force it into a different mode. You have to trust the way a poem comes to you. I don't expect it to happen, but I don't negate the possibility of my returning to a more formal verse tradition.

INTERVIEWER

Why do you suppose many young writers are almost embarrassed to write a poem in rhyme or metrics?

KUNITZ

Modern poetry begins for them with Williams and Pound (of the Cantos) and Olson and Ginsberg and Creeley—and they don't want to sound old-fashioned. It's a matter of conditioning. Furthermore, they see no reason why poetry should be difficult to write; they want it to be easy.

INTERVIEWER

Literary tradition has accumulated suspicions about the sincerity of any poet's feelings toward conventional subjects. There are certain poems of yours that seem oblivious to this. A poem like “Robin Redbreast”—until its ending—seems to strain sentimentally after the large problem of being a little bird, though its end is so powerful—when the robin is picked up, the poet sees the blue sky through a bullet hole in his head—that I am ashamed of my reaction to the earlier part of the poem.

KUNITZ

Maybe you're confusing pathos with sentimentality. My reverence for the chain of being is equivalent to a religious conviction. I don't apologize for my strong feelings about birds and beasts. Was Blake being sentimental when he wrote, “A Robin Redbreast in a Cage / Puts all Heaven in a Rage,” or “A dog starv'd at his Master's Gate / Predicts the ruin of the State”?

INTERVIEWER

Often your poems deal with dreams.

KUNITZ

Often a poem is a dream, but I don't necessarily say it is.

INTERVIEWER

Are there any specific poems that come to mind?

KUNITZ

The one that first occurs to me is “Open the Gates.” It begins with a vision of the city of the burning cloud. Like Sodom and Gomorrah—cities of the plain. Those images of dragging my life behind me and knocking on the door and the rest of it are straight out of dream. I woke at the moment of revelation, just when the gates were opening. Another source of that poem may be the Doré illustrations to Dante's Inferno, one of the magic books of my childhood. My images usually have an experiential root. In “The Testing-Tree” the image of my mother in the last section, the dream passage, goes back to a conversation with her in her eighties. She told me she had a proposal of marriage from a man of about the same age. He thought they should live out their lives together and take her off my hands; it was a practical thing. I asked her: “Do you really care for him?” She shook her head. “You know there are only two old men I have any use for. One's Bernard Shaw and the other is Bertrand Russell.” She meant that. Another image in that same section is of a sputtering Model A that “unfurled a highway behind/ where the tanks maneuver,/ revolving their turrets.” In '45, after my discharge from the army, I drove a Model A cross-country, stopping on the way at a little oasis in the middle of the desert called Silver Springs. A few days later I pushed on to the West coast. Several years later I drove back from the University of Washington where I'd been visiting poet. I took the route through Death Valley into Nevada to see my oasis. When I approached, armed guards appeared from every side and ordered me away. It turned out that the place was now Yucca Flat, the testing ground of the atom bomb. This is all curiously in the background of the poem, somewhat mysteriously translated. And the lines about “in a murderous time”: I wrote those lines the night that Martin Luther King was assassinated. I had been working on the poem for weeks, but couldn't get the ending right. I was visiting Yale at that time, reading manuscripts for the Yale Series, and staying with R.W.B. Lewis, an old friend of mine. We were listening to the radio when we heard about the assassination of King, with whom I had been associated, raising money for the civil rights movement. Suddenly, as I sat listening to the announcement, the lines I needed came to me.

INTERVIEWER

What is the source for the imagery of depreciation toward the end of this poem, such as the “cardboard doorway”?

KUNITZ

I see a movie set, furnished with memories like studio props. Doorways figure largely throughout the poem—entrances into my past, into the woods, into truth itself. I had recently gone back to Worcester to receive an honorary degree from Clark University and had asked to be taken to the scenes of my childhood. The nettled field had changed into a housing development, the path into the woods had become an express highway, and the woods themselves were gone. That's where the poem began, with the thought that reality itself is dissolving all around us.

INTERVIEWER

You indicate that with images pasted together like a collage?

KUNITZ

A montage, I would say.

INTERVIEWER

Can you say something about the arrangement of the lines for this poem?

KUNITZ

I started working with flush margins, and had difficulty achieving any sort of linear tension. Furthermore, I found the look of the page uninteresting, that long poem with all those short lines. I didn't develop a triadic sense until I began tinkering with the lines, as I often do at the beginning of a poem, trying to find the formal structure. The moment I hit on the tercets, the poem began to move.

INTERVIEWER

I am impressed by your capacity to break the tone abruptly or to shift the voice in a poem. Sometimes it is only for a line, but these outbreaks seem to have an idiosyncratic dramatic function.

KUNITZ

It's something I may have learned from working with dramatic monologues. In an extended passage I sense the need for an interruption of the speech flow, another kind of voice breaking into the poem and altering its course. I recall one occasion when I was hunting for a phrase to do just that, so that I could push the poem one step further, beyond its natural climax. My inability to achieve the right tone infuriated me. I must have tried thirty different versions, none of which worked. I was ready to beat my head on the wall when I heard myself saying, “Let be! Let be!” And there it was, simple and perfect—I had my line. If you have a dialectical mind like mine and if a poem of yours is moving more or less compulsively toward its destination, you feel the need of a pistol shot to stop the action, so that it may resume on another track, in a different mood or tempo. One of the reasons I write poems is that they make revelation possible. I sometimes think I ought to spend the rest of my life writing a single poem whose action reaches an epiphany only at the point of exhaustion, in the combustion of the whole life, and continues and renews, until it blows away like a puff of milkweed. Anybody who remains a poet throughout a lifetime, who is still a poet let us say at sixty, has a terrible will to survive. He has already died a million times and at a certain age he faces this imperative need to be reborn. All the phenomena of his life, all the memories, all the stuff that makes him feel himself, is re-materialized and re-blended. He's capable of perpetuation, he turns up again in new shapes. Any poem he writes could be a hundred poems. He could take a poem written at twenty or thirty and re-experience it and come out again with something absolutely different and probably richer. He can't excuse himself by saying he has written everything he has to write. That's a damn lie. He's swamped with material, it's overwhelming.

INTERVIEWER

What are your thoughts on the way you end a poem?

KUNITZ

My sense of the poem is rather classic. I think of a beginning, a middle and an end. I don't believe in open form. A poem may be open, but then it doesn't have form. Merely to stop a poem is not to end it. I don't want to suggest that I believe in neat little resolutions. To put a logical cap on a poem is to suffocate its original impulse. Just as the truly great piece of architecture moves beyond itself into its environment, into the landscape and the sky, so the kind of poetic closure that interests me bleeds out of its ending into the whole universe of feeling and thought. I like an ending that's both a door and a window.

INTERVIEWER

Your poems are packed; they have a weight. To me, it is a question of scale.

KUNITZ

Thanks. I've heard the opposite reaction, that my poems are too heavy. One critic wrote quite recently that my poems sounded as though they had been translated from the Hungarian. I don't know why, but somehow that made me feel quite lighthearted.

INTERVIEWER

Most of your poems are written in a high style.

KUNITZ

That used to be truer than it is today. I've tried to squeeze the water out of my poems.

INTERVIEWER

Is the elimination of understood words or definite or indefinite articles a feature of your aesthetic?

KUNITZ

I don't usually eliminate articles, definite or indefinite, but I've grown more and more committed to an economy of means.

INTERVIEWER

Mostly in your earlier poetry you have a stylistic habit of animating abstractions by hinging them to metaphors, as in the “bone of mercy” or the “lintel of my brain.”

KUNITZ

There's some confusion about this type of prepositional construction. When it has weak specification, when it incorporates a loose abstraction, it is a stylistic vice, and I've grown increasingly wary of it. I resist phrases like “stars of glory.” But when I say “the broad lintel of his brain,” I am perceiving the brain as a house. The brain is not, in this usage, an abstraction. It's just as real as the lintel. Pound was the first, I think, to define this particular stylistic vice, and modern criticism has blindly followed suit, without bothering to make the necessary discriminations. In any event, I don't accept arbitrary rules about poetry. Do you want to try me with another example?

INTERVIEWER

Take a phrase like “the calcium snows of sleep.”

KUNITZ

I like it, though I'm not the one who should be saying so. It's fresh and it happens to be true, scientifically true. During sleep the brain deposits calcium at a faster rate than when it's conscious. Besides, the “snows of sleep” have nothing in common with the “stars of glory.” The construction is legitimately possessive, analogous to the “snows of the Russian plains.” Sleep is where the snow is falling.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have a reading knowledge of Russian?

KUNITZ

No. I've described the method of these translations in the introduction to the Akhmatova volume. If I didn't have someone to help me with the Russian text, I would certainly be lost. I've worked mostly with Max Hayward, who understands what I want from him. I not only want a word by word translation, in the exact word order, but any kind of gloss that would be helpful to me, such as the meanings of a word's roots. The root sense of a word may supplement, or even contradict, its current usage. Etymology is one of my passions. I like to use a word in a poem with its whole history dragging like a chain behind it. Whether or not anybody else understands it doesn't really concern me. The word to me has a particular weight and historic validity. In the same way, I try to get from Max as much etymological information as I can. And then we go over the sound. We read the poems aloud. I translate only when I feel I have some affinity with the poet. Even with respect to a poet I don't feel particularly close to—Yevtushenko for example—when I was asked to translate some of his poems, I fastened on to some of his early lyrics, which are among the best poems he's written.

INTERVIEWER

What is the affinity you feel with Voznesensky?

KUNITZ

It was Voznesensky who got me started with the Russians. Andrei came to this country in the sixties and we met and had a good feeling about each other. How can I explain these things? He wanted me to translate him and I felt I could do it—again, selecting the poems that I wanted to translate. I enjoyed doing it, and I learned something too. Every poet I've ever translated has taught me something. One of the perils of poetry is to be trapped in the skin of your own imagination and to remain there all your life. Translation lets you crack your own skin and enter the skin of another. You identify with somebody else's imagination and rhythm, and that makes it possible for you to become other. It's an opening towards transformation and renewal. I wish I could translate from all the languages. If I could live forever, I'd do that.

INTERVIEWER

Many of the Russian poets you've known personally. Do you feel different about Baudelaire, whom you know only through his work?

KUNITZ

I know Baudelaire too—he was dealing with exactly the kind of issues that concern me. Problems of good and evil, the sexual drama. As a young man I was attracted to the violence of his inner life, the force of his rhetoric, and the hard structure of his poems, the way they build and make such a solidity of thought and image and feeling. In a poem like “Rover” I am very aware of my debt to him. The life of a poet is crystallized in his work, that's how you know him. Akhmatova I never met. She died in '66 and I never encountered her, but she's an old friend of mine in spirit. She taught me something, taught me the possibility of dealing quite directly with the most painful experiences.

INTERVIEWER

You are referring to the execution of her husband and the imprisonment of her son, as well as the government repression of her poetry?

KUNITZ

Requiem 1935-40 is a good example. The background of the poem was excruciating, and yet out of it she made a poem that is personal at its immediate level but universal in its ultimate form. It transcends the personal by viewing the historic occasion through the lens of individual suffering. Nothing is diminished in her poems: all her adversities and humiliations. She wrote with such burning and scrupulous intensity that she became part of the historic process itself—its conscience and its voice.

INTERVIEWER

Do you envy the disasters of other poets, even if those disasters lack the historical dimension of Akhmatova's?

KUNITZ

Sufficient unto each poet are his own disasters! The victims of history have a certain grandeur. One saves one's tears for those who fall victim to themselves. Their cries lacerate us. I'm thinking of Berryman, Sexton, Plath. . . . Perhaps it is in the nature of our age to be most moved by poems born of weakness rather than of strength. All the same, I yearn for an art capable of overriding the shames, the betrayals, the lies; capable of building something shining and great out of the ruins. The poets that seem most symptomatic of the modern world are poets without what Keats called negative capability. They do not flow into others. The flow of their pity is inward rather than outward. They are self-immersed and self-destroying. And when they kill themselves, we love them most. That says something about our age.

INTERVIEWER

The tragic sense no longer seems pertinent to our lives.

KUNITZ

The tragic sense cannot exist without tradition and structure, the communal bond. The big machines of industry and state are unaffected by our little fates. All the aggrandizement of the ego in the modern world seems a rather frivolous enterprise, unattached to anything larger than itself. Number 85374 on the assembly line may have a life important to himself and his family, but when he reaches sixty-five and is forced out of the line, another number steps in and takes his plate—and it doesn't make any difference. The artist in the modern world is probably the only person, with a handful of exceptions, who keeps alive that sense of the sharing of his life with others. When he watches that leaf fall, it's falling for you. Or that sparrow fall—

INTERVIEWER

The most difficult thing is that the adversary does not inspire confrontation. Evil has lost its cape and sharp horns. Hitler was evil but he was not a Satanic figure.

KUNITZ

The opportunity for confrontation with evil was greater in an earlier age. It becomes more and more difficult to intercede in behalf of one's own fate. The overwhelming technological superiority of the military apparatus protects the tyrant, as an emblem of evil, from his people. As Pastor Bonhoeffer learned, you cannot get at evil in the world. I've written about his moral dilemma when he joined the plot to assassinate Hitler. Evil has become a product of manufacture, it is built into our whole industrial and political system, it is being manufactured every day, it is rolling off the assembly lines, it is being sold in the stores, it pollutes the air. And it's not a person!

Perhaps the way to cope with the adversary is to confront him in ourselves. We have to fight for our little bit of health. We have to make our living and dying important again. And the living and dying of others. Isn't that what poetry is about?

* The actual quote reads: “I wish I could help you, for instance, by satisfying your desire to know from ‘what port,’ as you say, I set out. . . . The port from which I set out was, I think, that of the essential loneliness of my life.”